Speaking to Volunteers Outside the Ukrainian Embassy

- by admin

The situation in Ukraine is moving extremely fast so parts of this article may be out of date at the time of reading.

“I don’t really feel like I’m doing anything meaningful right now.” The reason given by one of the many men that came to the Ukrainian embassy to volunteer. Short, skinny and shaking, the 20 year old – who didn’t want to be named – lacked military experience and hadn’t told his family what he planned to do. He continued: “It’s a terrible situation and I just want to help.” A sentiment repeated by all of the volunteers that day.

On 24 February 2022 Russia invades Ukraine, in the largest military action in Europe since 1945. Three days later President Zelenskiy announces the formation of The International Legion For The Territorial Defence of Ukraine, and encourages “Anyone who wants to join the defence of Ukraine, Europe and the world can come and fight side by side with the Ukrainians against the Russian war criminals.” There has been huge volume volunteers, ranging from: Greying veterans dusting off their boots, private military contractors leaving well paid jobs, and a flood of civilians. From the start many were concerned that volunteers without any relevant experience, rather than helping the situation, could be a drain on resources and potentially lethal liabilities.

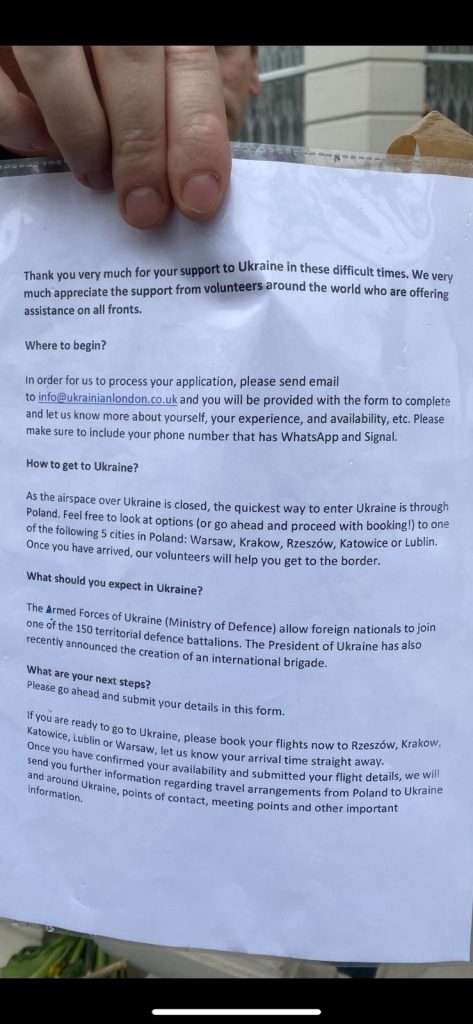

In Zelenskiy’s statement announcing the International Legion, people wanting to join were instructed to contact the Ukrainian embassy in their country. This was then repeated in a tweet by the Ukrainian Minister of Foreign Affairs Dmytro Kuleba and a – now deleted – Holywood style social media advert. Those that came to the Ukrainian embassy in London were met at the gate by a man in military fatigues who asked them to take a picture of a piece of paper printed with further instructions.

“I have seen footage of civilians … and yeah I think that’s really problematic.” The initial reaction of retired British Army Major Malcolm Hanson. He described three broad categories of volunteers, in descending order of usefulness: private military contractors coming as a preformed unit, individual retired soldiers, and civilians – “the loose coalition at the bottom, the people just turning up.”

Of the volunteers in London on 2 March the vast majority were in the third category: No military experience but, undoubtably, a lot of conviction.

Peter, 47, a former police officer from South Africa, gave a passionate speech in which he urged others to join him: “I hope you all get behind me, this country has been given tens of thousands of weapons. NATO can’t get involved, but we can.” He, like many others, talks about the civilians being killed: “These people are slaughtering families, women and children. I’m a parent, my daughter she’s 13, she doesn’t even know yet that I’m going. But I’m going to fight for her, her freedom.” After his speech Peter mentions that he doesn’t have a passport, but was hoping that border guards would be understanding and let him travel without one.

“Not being offensive to civilians but what a lot of them don’t realise is you are a human being on the ground, you are using things up, you are using up food, water, you’re using up loo paper. You’ve got to be able to justify your existence in that place. You become a staff problem because you now have to be maintained.” Said Maj. Hanson.

Callum Lawrence a 22 year old builder from Bow in East London, who had decided that morning that he wanted to go. When asked about any Military experience, he replied: “I’ve done some boxing and things like that.”

Hanson continues: “the problem with deployments is nothing needs to happen for people to start getting killed and injured … There’s lot’s of tired people, there’s lots of ammunition, there’s a lot of heavy machinery flying around, people get run over by things. People get accidentally shot.”

A man in his early twenties from Sunderland, Jack – who didn’t want to use his full name – had arrived with a backpack full of clothes and was under the impression that he would be taken straight off to Ukraine. After finding out that the only thing on offer was a laminated piece of paper with an email address, he said: “I’ve just come six hours on a train for that.”

Vinnie, 26, from Brighton had – a few years ago – attempted to join the British army but failed to pass training selection. He currently works in nightclubs but felt that “there’s a lot more important things to be done in the world at the moment.” He expressed a desire to not just be “sat terrified” and instead had an impulse to act. This feeling of wanting to get up and not just passively observe was voiced by many that day.

“Not that I would, but if I was out there and somebody said ‘okay Malcolm you’ve been in the military before, you’ve got three civilians with you’, I’d be thinking — and they’ve all got loaded rifles — ‘you’re not standing behind me.’ Because quite frankly you’re an unknown quantity and people die.”

Hanson talked about how the usefulness of people who had been in military was down to more than just their skills and training, but that they would form more coherently into units with trust: “I can imagine if you got a group of squadies together … within half an hour they’re starting to bond, you’ve got some commonality there … Because if one of them said ‘mate there’s a bit here where you might get shot at but I need you to stand there’ you need some common bond.”

There were a couple of ex British military among the volunteers that day: Jack Knight, who served in the Royal engineers, and Will – who only gave first his name – who a few days ago finished a five year contract in the army reserves. Will had already spent a lot of his own money on kit and had been sorting out legal arrangements – life insurance and writing up his will. He was also very open about how the fighting in Ukraine would be extremely dangerous, specifically because of Russia’s air superiority.

The foreign fighters that Hanson says will be most effective are private military contractors arriving together in sections (small self contained fighting units) that will instantly be able to work on their own: “I can imagine them formally going to the Ukrainian government and saying ‘Hey, [we’ll work for] reduced rates, we’re a squad of guys, we’ll go and do some work for you.’” They would already have strong bonds and trust, as well as their ability to work semi-autonomously mitigating language barrier issues.

One such group was interviewed by the Guardian in Ukraine at Lviv station, waiting to board a train to Kyiv. From the group Ben Grant – son of Tory MP Helen Grant – spoke on camera, and iterated many of Hanson’s points. Grant, former Royal Marine, has been working as a private military contractor (PMC) in Iraq.

Another member of the group of seven, going only by the name Jax, said: “I left £4,500 a month to come here.” Implying that he hasn’t come to Ukraine for the money, but Hanson speculates that a PMC might not only be there for either a pay check or on humanitarian grounds: “you might still want to go to make your mark … to cut your teeth, to show who you are, for any number of reasons.”

On 13 March Yavoriv military base, housing an estimated 1,000 foreign fighters, was hit by 30 Russian missiles, Ukrainian officials have said that 40 soldiers were killed and 135 injured. However a German volunteer who was at the base – quoted in Austrian newspaper Heute – said that the Ukrainian figures only included their own citizens and that over 100 foreigners also died. The Mirror reported that a group of at least three British ex special forces were feared dead in the attack.

The base, only 15 miles from the Polish border, was a key training facility for foreign volunteers – Ukrainian official Roman Shepely was quoted in Reuters: “They all end [up] in Yavoriv, and from there they are distributed to the points of service.”

There has been no official statement on how many foreign fighters are currently in Ukraine, but on 7 March the Foreign Minister, Dmytro Kuleba, announced that 20,000 people from 52 countries had contacted embassies to volunteer.

On the day that President Zelenskiy announced the formation of the International Legion, British Foreign Secretary Liz Truss – in an interview on the BBC – said that she was in support of people deciding to join. On 9 March Truss walks back on her statement after she had been contradicted by both PM Johnson and Defence Secretary Ben Wallace.

Some British citizens that have gone to Ukraine have reported back that the fighting has been extremely intense, and many volunteers have already returned home. For anyone considering joining the International Legion Major Hanson has a closing message: “If there’s a civilian foreign fighter who doesn’t know what’s coming they’ve got a real shock, because if it does descend into chaos, if you’ve got no staff officer making sure you’ve got food and water, you’re now on your own and in a bombed out city there are no more rules. All the rules are off, and that’s an utterly different, you really have to know why you’re there if that happens.”

The situation in Ukraine is moving extremely fast so parts of this article may be out of date at the time of reading. “I don’t really feel like I’m doing anything meaningful right now.” The reason given by one of the many men that came to the Ukrainian embassy to volunteer. Short, skinny and shaking,…